NOTHING MORE REAL THAN THE IMAGINATION

A CONVERSATION ABOUT THE CREATIVE WRITERS WITH W. D. CLARKE, PART ONE OF FIVE

Nothing More Real than the Imagination

A Conversation about The Creative Writers with W.D. Clarke

Or, A Lie-Detector Test for Four Hands

“Oh! how immaterial are all materials! What things real are there, but imponderable thoughts?” Hermoine Melonville, Moby Dick (Chapter 127)

WDC: First off, Gary, congratulations on this blisteringly inventive novel of yours. I've quite literally never read anything like it (my experience being similar to [main character] George's own first reading of Gravity's Rainbow (“The neurons fire exactly like my vintage 1957 Mark 2 anti-aircraft gun. A screaming comes across the sky of the brain.” “You were thinking Pynchon. Everything else was a blur.”) —something I feel is somehow related to the title that you chose for this little talk of ours...

GA: As William Carlos Williams put it, “everything depends on the red wheelbarrow, glazed with rainwater, beside the white chickens.” I take this to mean everything depends on the imagination.

Two thoughts: A) Human consciousness, not just civilization, depends on our ability to imagine. We all have a tendency to dismiss the imaginary because it's not real, in the sense that you can't put anything in the wheelbarrow, and the chickens don't need to be fed. I can hear my yeoman farmer grandparents—sophisticated and sympathetically intelligent people—urging me to keep my feet on the ground and deal with "what is," with what can be apprehended by the senses. The boy whose head is lost in the clouds is in real danger, because, well...life is pretty awful. One must be alert and cagey! Every Man for Himself and God Against All, as Max Stirner and Werner Herzog put it!

B) People live their lives according to beliefs. They imagine something to be true and will justify any atrocity on the grounds of that belief, religious or otherwise. What we call "art," "religion," and "science" are only the demigod offspring of the Creator, Imago. There's clear evidence that at least a million years ago, Homo sapiens were confronting each other over the things they were seeing in their heads—especially when asleep. Even my grandparents would say at times, use your imagination, which meant be resourceful.

WDC: Sounds like your Super Yin and Super Yang in the novel, taken together. Nothing more real in two senses, then: the imagination is as real as (and important, and superlative, and thus linked to) any other human faculty AND dismissible as a flight of Fancy, however justly or un-, by nose-to-the-grounders. It's been a while, but I remember the term Fancy being derided by 18thC Enlightenment types such as Locke and other empiricists as being but a necessarily AI-like reconfiguration of sense data (as in fanciful animals like Hippogriff or Chimera being just bits of animals we've seen). When we get to the Romantics, however, there is a sense that it has, or can have...superpowers?

GA: Yes, it makes one wonder just how enlightened those chaps actually were. What did they think—what did they imagine—was going on in their heads? It's inarguable, of course, that some "products" of the imagination are silly, just as a "transcript" of the stream of consciousness is mostly incoherent babble (see Emile Cohl below), sounds and images floating to the surface and popping like bubbles...and there's Michaux (epigraph also below) actually trying to transcribe what he called "the unbearable repetitions." It's a little like small-talk. But small-talk is also talk. Its smallness doesn't take it outside the set of talk, just as daydreams are, in my view, absolutely inextricable from more rigorous and consequential thoughts. Joyce proved that conclusively--unless some anal empiricist wants to dismiss novels, and all art, too. (And they do. Daniel Dennett leaps to mind, the Dick Cheney of cognitive science.) But however airy-fairy the imagination can seem, it's every bit as concretely physical as a stone: electricity and bio-chemicals have mass. It's all rearranged sense-data; what is not? What's really interesting to me is that out of all that fiery stew, hippogriffs and chimeras do appear. It is miraculous. It is magical. It is a superpower. Human consciousness, hyper-consciousness, meta-consciousness: this is the infamous "hard problem," right? But it's also so easy an infant can do it. And it's absolutely free. No salesman will call at our homes.

W.D. Second, could you comment on your novel's subtitle ("A BURLESQUE OF THE IMAGINATION ON TOTALITARIAN THEMES IN THE MANNER OF ÉMILE COHL & LES ARTS INCOHÉRENTS, HARRY EVERETT SMITH & HANNA-BARBERA")

GA: If the imagination is as serious a capacity as I've suggested, it is nevertheless productive of sublime dopiness. I'm not at all sure how laughter and imagination are related, but I do know that if you take yourself, i.e., your imagination, too seriously, you're a clown, a fool. Shakespearean fools are famous for speaking truth to power, but generally fools are dangerous Machiavellian entrepreneurs. Nothing is more life-giving than laughter, and nothing more dangerous than someone who cannot laugh at themselves. So when I say that my novel is a burlesque, I mean what the dictionary says:

"A burlesque is a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects. The word derives from the Italian burlesco, which, in turn, is derived from the Italian burla – a joke, ridicule or mockery."

I am partly mocking writers and readers who insist on the conventions of realism—not to mention the anti-fanciers above. If you want to call on Balzac and "the representation of reality," I can only applaud. I have nothing against it. I am not a rebel. I love Balzac (who I first read, tellingly, in a history class). But man, it's easy to abuse realism. Like any drug. You get addicted to conventions and suddenly conventions are virtues and unassailable in their primacy. Writers and readers beat their imaginations to death because “that's not the way you're supposed to do it.” Life drips away, all thoughts of form are pro forma, and lifelessness is understood as comforting, reassuringly free of disturbance, an escape from the unpredictability of murderous life into the predictability of cozy murder mysteries.

The imagination does not recognize boundaries, formulas, or conventions. What makes it to the published page, when all thoughts turn to the question of what will people buy, recognizes little else, but imagination lives and works in chaos. We all know how relentlessly, entertainingly, and violently it demonstrates its power over our psychological regulatory mandates.

Which is not to say that so-called experimental art is necessarily better; it too vexes the imagination with seemingly pointless exercises in abstraction and meta-constraint. Which reminds me of a story Gregory Bateson often told:

"A man wanted to know about mind, not in nature, but in his large private computer. He asked it (no doubt in his best Fortran), 'Do you compute that you will ever think like a human being?' The machine then set to work to analyze its own computational habits. Finally, the machine printed its answer on a piece of paper, as such machines do. The man ran in to get the answer and found, neatly typed, the words: THAT REMINDS ME OF A STORY."

My story is of walking with the British author Alan Burns after the one creative writing class I took as an undergrad. He was, and remains, one of the great exponents of postwar experimentalism, along with his friends, B. S. Johnson and Ann Quin, and I told him that I too wrote experimental fiction (I was twenty). Then he stopped me cold: experimental, he asked, in what way? I blushed and mumbled and said: I've never done it before? He then suggested I read William Bez. Bez? I asked. His accent was thick and strong, and the name turned out to be Burroughs.

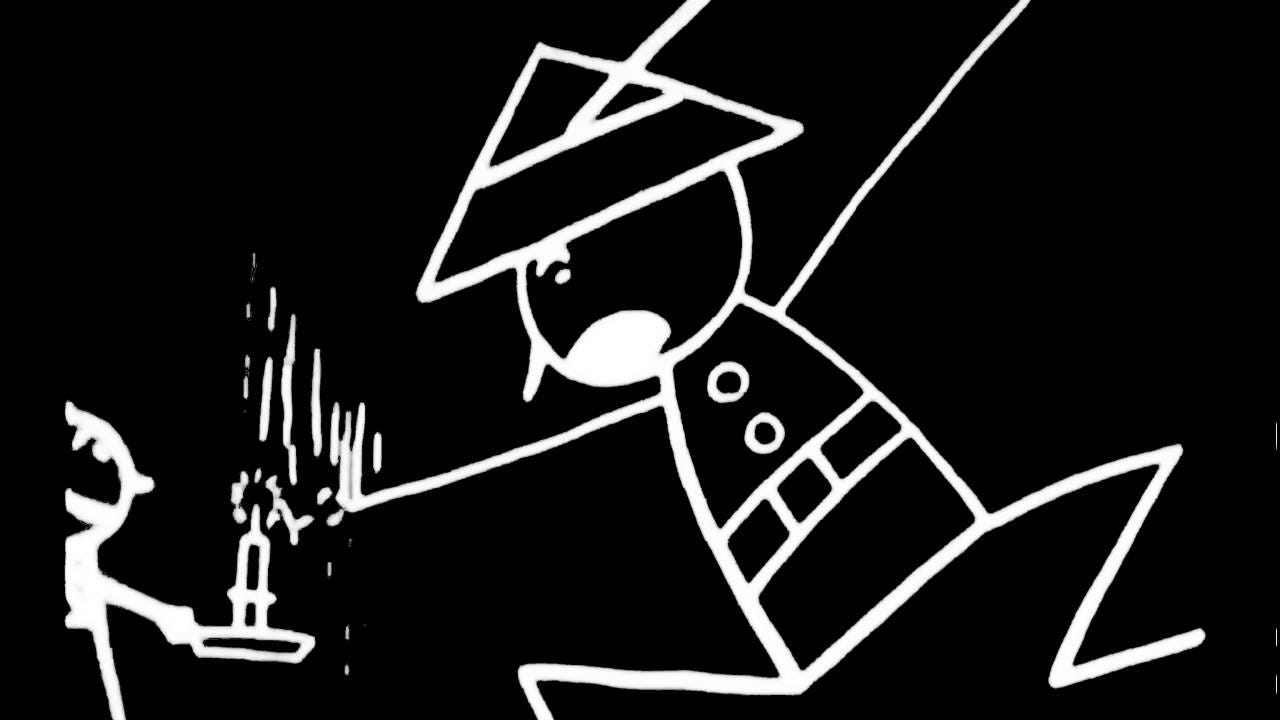

This novel is, simply put, something I've never done before, in which I mimicked the reckless speed of imagining. The references to Harry Everett Smith and Hanna-Barbera are easily explained. Smith's Heaven and Earth Magic (Bob Dylan's favorite movie for a time) was a movie I had running before every class I taught. It's bizarre and shapeless and I wanted to knock—and succeeded in knocking—my students off-balance. Hanna-Barbera: two of my main characters, George Joutsen and Frederick Funston, become Jetson and Flintstone. Both of those character names preceded The Creative Writers (in an abandoned manuscript, but a "George story" will appear in the new issue of Santa Monica Review), and I honestly did not see the connection to the cartoons until later. Emile Cohl (1857-1938) was a French caricaturist and satirist, a founder of the Incoherent Movement, and "The Father of the Animated Cartoon." I stumbled across some stills from his 1908 Fantasmagorie. One of them was of a gigantic clown figure menacing with a sword a much smaller figure, who is holding a candle. I thought immediately of Wallace Stevens's "scholar of one candle" ("Auroras of Autumn"), and Big Publishing.

WDC: In that poem the "scholar of one candle" appears at the end of section VI, just before an important question is asked at the beginning of Section VII, viz.

“This is nothing until in a single man contained,

Nothing until this named thing nameless is

And is destroyed. He opens the door of his house

On flames. The scholar of one candle sees

An Arctic effulgence flaring on the frame

Of everything he is. And he feels afraid.

VII

Is there an imagination that sits enthroned

As grim as it is benevolent, the just

And the unjust, which in the midst of summer stops

To imagine winter?”

If our scholar is the solitary reader (or writer) in the era of Big Publishing (and, in the context of Ch. 2ff in the novel, Hollywood, of course, and broligarchs of the likes of your character Ike Perlmutter, etc... is The CWs then a kind of exemplar for how to go about doing battle with the likes of such sword-wielding clowns, even in the midst of our houses burning down and the polar vortex blowing through our everything else?!

GA: Sure is nice to think so. I certainly don't know, and don't even have an idea of how to begin to know. I do know, or at least believe/imagine/think I know, that it's quintessentially human and has seen us through a million years (I refer to the site of the first controlled interior fire, in Wonderwerk Cave at the tip of South Africa) of terror and love. But here's a final question: why would Big Publishing want its customers to be sedated enough, and enslaved enough, to put up with mass-produced uniform entertainment products--apart from predictable profits? You'd think they'd want customers to be wildly imaginative, to be eager for the new and the weird and the whatever, but they don't.

WDC: I'd also like to linger a bit on an earlier part of your above long answer, specifically on:

“But man, it's easy to abuse realism…” Having taught in a Creative Writing department at a university, do/did you feel like the work you and your colleagues did there was in service of the imagination, or in beating it to death, on balance? Obviously, parts of the MFA-world are in the sights of your satire/burlesque, but—would you do it again? If called upon as one of those highly-paid consultants, how might you advise them to either continue "fighting the good fight" else change their ways, repent, repent?!

GA: Wow. What a great question. I have said through my teeth a thousand times that I would never debase myself like that again. (I mean, honestly, I took a savage reputational beating, was deprived of 7K a year we rather needed (need!) and I lost library privileges!) But I did like teaching. At least aspects of it. Moments. I was doing what I would do even more vociferously if I had the chance you posit: conduct another phase of Martin Amis's War Against Cliche. That's what I was doing with the assignment described in the novel, "How to Be Happy and Succeed in Life": entertaining the living cliche out of them. It would be hard for me to prove it (and yet I could), but you would not believe how liberating some of the students in my classes found that war to be. I don't mean just cliches of language, but of social wellbeing. I could see them stopping in their tracks and... thinking again. Light bulbs all over the place. Sound of flashbulbs crackling. A different look in their eyes. A sense of what was at stake.

To answer specifically the first part of your question: my former colleagues were working in the service of the imagination. They are all good writers, and their classes were often well-taught and valuable. We all (I mean everybody everywhere, not just my former department) went into teaching with the best intentions: talking about literature and why we want to be in its service--why we must be in its service, no matter the obstacles—including the opprobrium of our loved ones!

But MFA programs and undergraduate majors swiftly proved to be monstrous engines of conformity. The experience of Writer X and Y and Z who found the classes rewarding and who are writing good novels now pales in comparison to the metastasizing disease of creativity profiteering. This isn't the place to trot it all out, but we can call it middlemanism: people who insert themselves between source and product, between writer and dreams of popular success (or just a kind word) thumbing their noses at the absolute truth that reading and writing are solitary occupations of individual imagination. Organizations who, for example, run programs like "One City, One Book," where everybody reads the same book: that just yanks seedlings of organic imagination out of the ground and stomps on them. It's just barely this side of religio-fascism. "One City, Ten Thousand Books"!

We're seeing socio-politically how insidious "democratization" can be: you can be a grotesquely stupid villain and become the most powerful person on Earth, when what a person actually does matters less, or not at all, than what they say they're doing. When everybody is a writer, rewards must be handed out in corrupt and disingenuous ways. Very few people are artists and man they are born that way and they suffer for it. All the cozy seminar rooms looking out on evocative landscapes with ASMR sounds in everybody's earbuds while their hurt feelings are acclaimed as literature can't change that.

MFA-ism (mother-fucking-asshole-ism?) is only a third of the problem, though. While those programs were expanding, independent bookstores were being driven out of business. I saw that firsthand too, having worked for three really good indies, with national reputations: Hungry Mind in Saint Paul, UConn Co-op in CT, and Dutton's Brentwood in LA. The chains stocked their stores with every book ever published, got customers with cheaper prices, then tossed everything but the bestsellers. At the same time—in cahoots—publishers were swallowed up by entertainment conglomerates who had huge overheads and who demanded profit margins ten or even twenty times what they had been. Thus was the creative-industrial complex born, with programs cranking out grads to supply the need for more of same. The current dominance of YA and—ghastly neologism—romantasy fiction was easily foretold. AI can and will do it.

Finally, though, to return to the question, what I found immoral, cowardly, and yes even criminal in my colleagues was how easily they capitulated to corporate fears of "legal exposure," and abandoned me to the lawless administration. So, whatever else may be said, I end this way: fuck them. Whatever we thought at first, the university has proved to be no place for artists. Martin Amis nailed it: "The novelist cowers in the boiler-room of the self, where he works in his stinking singlet, his coccyx-baring jeans."

WDC: You chose some interesting epigraphs for the novel as well. I think they deserve some unpacking!

GA: Kafka would take one look at a class of creative writers, and his head would fall into his hands. He would weep convulsively until it turned to laughter, as it must, eventually, one way or another, quickly and infectiously becoming hysterical. The orgasm of the laugh. He would shout "Coming-of-age tales set in plausible fairylands?" He would then walk out, with pity but without a word, and write "In the Penal Colony II: Marketing the Skin of the Dead Artist."

The Arendt quotation speaks to what I was saying above about the uncontrollability of the imagination. The creative industrial complex is very serious about protecting us from reality. It's the easiest way to totalitarianism. Bread and circuses. Nothing new. But much more powerful now that the internet and AI have isolated us, sedated us, and severed from our brains everything but the paleomammalian cortex.

Michaux's Major Ordeals is one of his books about mescaline trips, the most well-known of which is Miserable Miracle. He was not in the least a drug-enthusiast, and I think even eschewed alcohol, but he was very interested in hallucination--as in nothing more real than--and would get high and try to take notes about and draw sketches of what he was seeing.

"In the huge light churn, with lights splashing over me, drunk, I was swept headlong without ever turning back." "Trace the passage of image into thought." "To all my efforts to prove that none of it was true, since I was here in my own room which I recognized with all its familiar objects, it [mescaline mind] would reply by manufacturing new episodes, insane and contradictory, but so instantaneous that I had hardly a second to parry them before the next one, which had to be answered victoriously, was hectoring me, seizing me so that, with the key already lost countless times, and in the face of actual proofs, even my room, my books right before my eyes were lost in their turn, were immaterialized, and, even when I looked at them again, they could no longer command my attention, could not emerge out of the abyss of the successive engulfments and buryings."

END PART ONE