“Audience is instructed to leave theater.” George Brecht, Word Event

I was born and raised in Minnesota, and still browse the state news. I spent ten of the thirty years I lived there in the theater, in a little Golden Age, when money flooded the arts and arts administrators really came into their own[1]. They offered sips of corporate art Kool-Aid to playwrights, actors, and directors, and what had begun as Off-Broadway and Off-Off-Broadway in the 50s and 60s, crawled off to die in their and other League of Resident Theatres offices around the country.[2] So it was with the heightened awareness of fight-or-flight decision-making that I read this article a few months ago in the MinnPost: “Study investigates mental-health themed musicals’ ‘significant’ toll on performers”.[3]

The article was as brief as it was disturbing, so I looked up the paper and project which it described. It was written by Dr. Michelle Sherman, a prof in the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health at UMN. Here’s the abstract:

“The popular stage musical, Dear Evan Hansen, will be released in movie theaters on September 24, 2021, giving the general public access to this powerful production which vividly portrays topics of suicide, depression, and social anxiety. Numerous musical theater productions (such as Les Miserables and Next to Normal) and movies (such as 13 Reasons Why) have addressed themes of mental illness, but minimal research has examined the impacts of such portrayal on both the actors and audience members/viewers. Such intense depictions of mental illness may have both positive and untoward effects. For example, although some audience members may feel validated and less alone when seeing their experience in the media, others may be triggered. In fact, research in both the USA and Canada found significant increases in rates of suicide in teenagers in the immediate aftermath of the release of 13 Reasons Why (Bridge et al., 2019; Sinyor et al., 2019).”

That’s quite a leap from Victor Hugo to Brian Yorkey, but never mind. I next found a note of caution about the Bridge study, from Daniel Romer,[4] Research Director at the Institute for Adolescent Risk Communication at the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania:

“I found that the increase for boys observed by Bridge et al. in April was no greater than the increase observed during the prior month before the show was released. In total, I conclude that it is difficult to attribute harmful effects of the show using aggregate rates of monthly suicide rates. More fine-grained analyses at the weekly level may be more valid but only after controlling for secular changes in suicide that have been particularly strong since 2008 in the US.”

The problem, then, is children committing suicide? Tracking and analyzing stats is certainly part of good science, and so is hypothesizing hidden or distant causes as possible explanations of baffling and shocking effects. It’s also clearly important to confront the means by which we are, to use Neil Postman’s phrase, amusing ourselves to death. The idea, however, that children who aren’t already suffering terribly can be moved by some cheaply manipulative Hollywood/ Broadway crap to kill themselves is hard to take seriously as a conclusion. It strikes me as perverse, and smells of marketing. I turned in dismay to Sherman’s bio:

“As a psychologist, choreographer, and long-time fan of musical theater, the opportunity to merge my passions for psychology and theater and engage in robust discussions with theater professionals has been meaningful and enjoyable. Study participants shared that audience members who struggle with mental health concerns can feel less alone when seeing mental illness portrayed on stage; theater can spark discussion and personal reflection about mental illness, decrease stigma, build empathy for people living with mental illness, and even encourage activism. However, viewing mental illness on stage also has the potential to be distressing.”

So…damned if you do, damned if you don’t?

“Public Significance Statement: Sparked by the awareness that many musical theater productions powerfully address themes of mental illness, interviews with 15 theater professionals were conducted; participants shared how theater can evoke strong emotions in both performers and the audience, can give people experiencing mental health challenges the experience of being ‘seen,’ and can open dialog and decrease stigma surrounding mental illness. The study introduces the role of a Behavioral Health Consultant (BHC) who can support the production team and audience in many ways.”

Some of the fifteen had Equity contracts, so it wasn’t quite Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland[5] exhorting their friends to “put on a show,” but when that image—more Dorothy in Oz than in Babes in Arms—lodged in my head, I began to see the problem in a different way. Every one of the fifteen professionals would jump at every chance and hurl themselves through every flaming hoop, not just in hopes of seeing their name in lights, but simply for a shot at another part, knowing—this is the catch—that there will be a psychological price to pay because the machinery of the mind can’t be operated cheaply. Just ask Facebook, and the millions of girls who are already as damaged as Judy Garland was without having set a foot on a stage. Or any successful actor: they probably won’t be able to answer except according to scripts handed out to them from their publicity people, but between the lines and in their eyes, you will sense the truth.

There is a joke about this truth, and it goes a little something like this: Three dogs are given piles of bones. The mathematician’s dog arranges the bones in a series and sniffs them one after another repeatedly. The philosopher’s dog arranges the bones in a circle, and trots around them until he’s dizzy and confused. The actor’s dog eats all the bones, fucks the other two dogs, and asks for the rest of the night off.

The theater is Dionysian. Tragedies were odes written for actors dressed up in goat-skins to signify their satyr origins. The followers of Dionysus were famous for their passion—a word that has nothing to do with that hobby you are trying to convince yourself you enjoy, but suffering: the patient, patience, passion, all depend on suffering for their meaning, a suffering that was supposed by tragedians to reach beyond itself, in a fever, to ecstasy, to ek stasis, an out of the body experience, to enthusiasm, which is possession by a god. If you weren’t careful, you might be rent in a hundred pieces by these ecstatic enthusiasts of the theater: they did it to bulls every day, and even did it to Orpheus.

In addition to Zoom calls, Sherman visited the cast of Next to Normal, which was produced by a “youth-focused community theater group” in a suburb of Saint Paul. The cast seems to have thought that because the play was intense and disturbing, they felt intensely disturbed. “They talked about the emotional toll of being in the plays,” Sherman said. “Many talked about going offstage and crying and having real difficulties separating their role and their personal life.” Nothing wrong with that. Pretty much SOP. A friend of mine was in a production of Arthur Kopit’s Indians (Robert Altman adapted the play in 1976 as Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson). The American Indian Movement superstar Russell Means gave a talk during a rehearsal, and my friend said he instantly began hallucinating that he was actually an Indian, and swore he would only eat wild rice as long as the show ran.[6]

The director of Ashland Productions’ Next to Normal was a young man named Cullen Wiley. Here’s what he said: “We had a lot of conversations about mental health and our experience with it and how it is important to not just take care of yourself but also take care of others. We created a really safe space where we had a safe word. If we were in the middle of a scene and it was too emotional or too tough for the actors, they would say the word and walk away for five minutes, collect themselves and keep going.”

This seems to have been a drama within a drama, acted out in rehearsals with no more and no less sincerity than the play itself. There never has been a rehearsal without actors acting out personal feelings disguised as concerns about the production, but this is different. These safe words and time-outs are coded advertisements about who is more vulnerable, moved, and closer to the edge that marks the plummet from feigned actions onstage to real psychological danger and real consequences offstage. They are advertisements of moral courage, and possibly, moral one-upsmanship as well.

Another version of this kind of advertising is the warning that preceded the second season of 13 Reasons Why.[7] This appears to have been appended after some complaints that the show glamorized suicide. The show’s stars introduce themselves and say which role they play, then urge viewers to get help if they need it: “Watch our show,” one says, “with a trusted elder.” It’s hard for me to imagine anything more disingenuous.

Because the theater is a crucible for understanding distinctions like ingenuousness/disingenuous and real/fake, let me examine it for a moment: people who are disingenuous are “giving a false appearance of simple frankness, honesty, sincerity.” They are “calculating.” But isn’t that a fair description of how theater works? It most certainly is. That’s why actors train and rehearse: to learn how to appear this way or that way in the service of the director’s calculation of how best to show the play to an audience. Adults are at least able (if all too often unwilling), for instance, to hear that Celebrity Actor X, known far and wide for her deep humility and sympathetic intelligence as Character Y, is actually a tremendous asshole and shockingly stupid, her dim wit devoted wholly to calculation. And there’s that word again. I guess the calculated appearance of sincerity can be both good and bad—or rather, neither good nor bad, since it’s simply a feature, like all the others, of human conduct. Dissimulation is a way of presenting something that’s not immediately to hand or intrinsic to the presenter. The glamorous young actors, on top of their world, who presented the warning to viewers yearning to be like them, dissimulated compassion, but was it not in the service of concern for the wellbeing of others? Maybe, maybe not. I think they did it because they had to, because creator/writer/director/executive producer Brian Yorkey (who, I should point out, won a Pulitzer for Next to Normal) made it perfectly clear to them that there was a lot of money on the line. And I think that they, as child-careerists, had no trouble accepting that. They were having a great time playing depressed and suicidal teens. Is it wrong of them to enjoy their good fortune? Not at all. But there is something wrong here.

As middlemen in the supply-chain of the creative-industrial complex, they are just doing their jobs. But are they doing their jobs as artists? Not at all. When you feign compassion in the marketplace, you do so without dignity. What is dignity? It’s a natural state and, like authenticity, hard to lose—unless you are engaging in violence, or the violence of buying and selling. (If you’re buying something you need, of course, and the seller isn’t trying to screw you, there is ordinary dignity in the transaction.) But can you feign compassion with dignity on a stage? Yes, you can. That’s why theater was invented. Dignity inheres in honesty and honesty inheres in art. So the question is this and this only: what is your feigning in the service of? The actor knows, always knows, and either listens and cares, or doesn’t.

The audience knows, too, always knows, and either cares or doesn’t. But here’s a little trade secret: the medium in which the transmissions take place is clearest and sharpest and most conducive to the nuances and subtleties of the truth when actors and audiences have a healthy disregard for each other. In our age, one of unparalleled adoration of celebrities, with the story in the service of the actor and not, as it must be, the other way around, we won’t find many teenagers or teenaged adults willing to do anything but worship their popstars. Likewise we won’t find many performers willing to do anything but pander—usually in the lucrative decry/ pander mode: isn’t mental illness, bullying, injustice, loneliness, deceit, and despair the last thing you want to think about, having endured so much of it in real life? We feel just like you do, trust us, we get it, and that’s why we’ve made this play, TV show, movie, that allows us all, together and united against hate, to wallow in all that terrible, hurtful stuff because know we’re indulging ourselves in a good cause.

In a healthier time, actors were often heard to say that the audience gets the show they fucking well deserve.

A healthier time? Well, Nietzsche put it this way: “Euripides hadn’t the slightest reverence for that band of Bedlamites called the public.” And Euripides said this about a character he’d dreamed up called Herakles: “There he stripped himself naked and engaged in a wrestling match with no one, proclaiming himself victor over no one, bowing to an audience of no one.”[8] The scene is of Herakles, struck mad, murdering his children, but there’s more to Euripides than Xtreme melodrama. His point in those lines is surely that spectacle is an emptiness into which spectators pour their feelings, and, more importantly, that the engineer of the spectacle, the actor, is utterly alone. Even if he wanted to care about the audience, he can’t, because his mind is elsewhere. Certainly he knows they’re out there, and when they applaud, he will bow and beam and blow them kisses, but even as he reverently puts hand to heart, he actually couldn’t care less what they think. He wants to eat and get laid and swozzle himself to sleep with whatever drug is to hand. What his mythopoetic publicists have to say about it is meaningless in the face of actual living.

And that is how it should be. People put on a show, other people watch it. The more they care about (i.e., want to control) each other’s thoughts and feelings, the more infantile they become. If you read Robert Brustein’s reviews from the late 50s to the late 70s, one of the clearest themes is a lament for the loss of the kind of theater-goers who saw plays regularly and took them all in stride: they wanted to see something they’d never seen before, something new and different, and were happy to take the good with the bad, because live theater was always exciting anyway. They could make up their owns minds, and would have been at best bemused by any attempt to prepackage the experience: here is what you’ll see, and here is what you should make of it.

But let’s return to Cullen Wiley. He’s heard criticisms from “theater old timers” who insist that “the show must go on,” struggling through performance after performance without special supports like trigger warnings, safe words or behavioral health consultants.

“I personally don’t like that saying,” said Wiley. “I think it’s really outdated. We’re entering a phase where we’re putting ourselves first. If someone broke their leg onstage, it would be OK to stop the show, get situated and have someone else go on for them. In the past it was, “You’ve just got to suffer through.”[9] But it’s not safe. We’re a lot more safety conscious these days, which is good.”

It has nothing to do with safety, though. For all the goofy excesses of actors, the theater is not a dangerous place. It’s precisely the opposite and always has been. The only time it’s not is when political judgments interfere with aesthetic ones. Those measures Wiley and his cast took, and the trigger warnings posted in the lobby, were, as I said above, advertisements, but not just ordinary ones. These advertised a very special sort of show. The show wasn’t about mental illness in suburbia, it was about how difficult it is do a show about mental illness in suburbia. It was a show about how near the cast, this particular cast, drew to despair and madness in a selfless drive to be of help to suffering people everywhere, and the price they paid.

It was a show about a self-referential loop, the so-called “strange loop,” or a tangled hierarchy (no matter where you go, there you are), or maybe just an infantile mise en abyme. I don’t mean simply a play within a play; I mean a play within an advertisement for a play. The advertisement is what you pay for, and the play is a bonus gift for supporting cast and crew. If the thing being sold is bought, the proceeds don’t go to the production of a new play, they go to a new advertisement, for another play about how hard and dangerous it was to produce the kind of plays they produce. Every time they come around the loop, they want the play to be more about them and less about the characters. If transit of the loop is successful, the next transit will be better funded and more people will see it, over and over again until they are as powerful as Brian Yorkey and they can laugh at their hypocrisy all the way to the bank. But it will always be the same transit, the tragedy of having acted in a tragedy, dollars flying off or floating in, uniform and predictable, dishonest and lucrative, aping art but never knowing the difference, perfectly totalitarian in its regard for the people.

The show has to go on because, as Julius Marx put it, remembering the time in 1905 when he was stranded in Grand Rapids, Michigan with the Wangdoodle Four (a Black quartet who disguised themselves as Chinese): “I didn’t have enough money for either a room or a train ticket.” Plays are jobs. If you are lucky enough to get a job, you do the work, no matter how glorious or pathetic, dirty or glittering it is, and you move on to what you always hope will be another job.

Of that hard work, Dr. Sherman had this to say: “Actors work hard to embody and personify their characters. If they just pretend to be a character, their performance is not genuine.” Actors “really want to portray the illness accurately. They have to get in touch with that emotional internal experience to portray a character accurately on stage.”

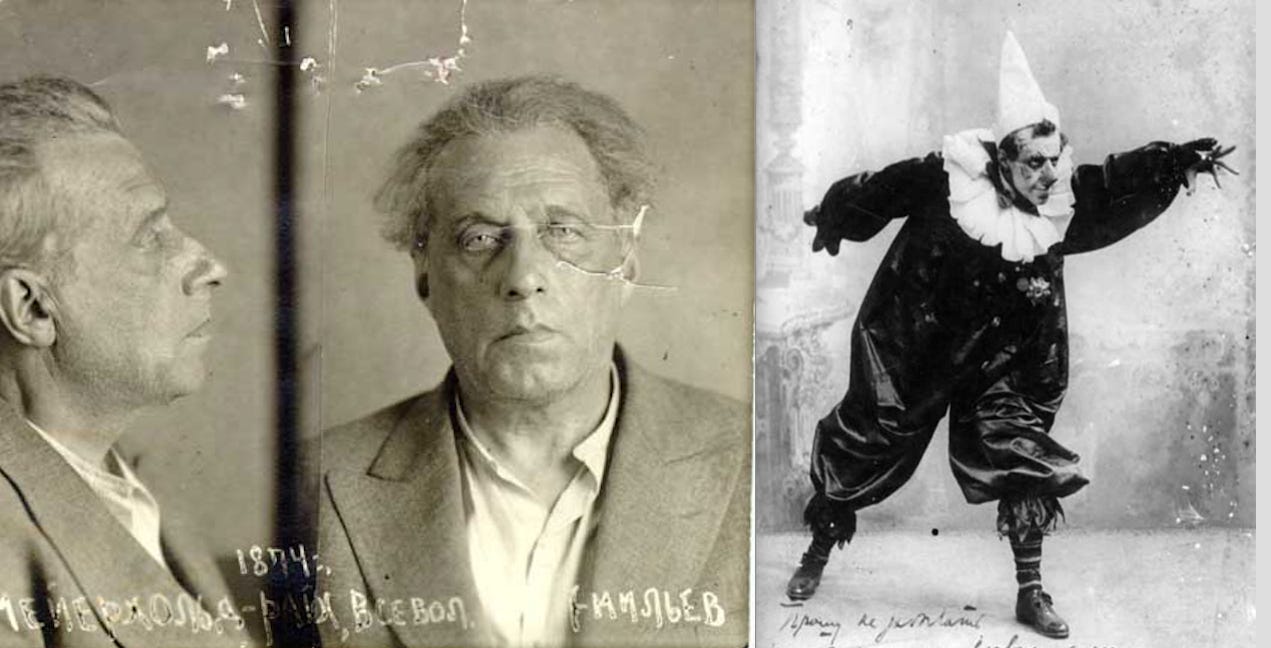

Easy to know where to start with this, and end. It is completely wrong. It is so wrong that the whole of human dramatic enterprise from Blombos Cave a hundred thousand years ago to the next show at the Old Log Dinner Theater in Excelsior Minnesota on the shores of fabled Lake Minnetonka rolls in its grave and eerily snickers in protest. Pretending is precisely what actors do. Getting in touch with “emotional internal experience” is what happens along the way as actors learn how to pretend better, sometimes with the aid of a method like Stanislavsky’s, most often in the way little children do: decide what looks right and sounds right, and you’re done. Just imagine how frightened everyone would be if a real hallucinating schizophrenic were to enter stage left. Or consider this photo of Liz Taylor freaking out in Suddenly Last Summer:

And this one pulled back a few feet:

Or listen to the dying Artaud.[10] His call for a “theatre of cruelty” was not a call for actors to lose their grip, take shits on stage, and fling it at the audience while singing “Let Me Call You Sweetheart.” It is a call to see that impolite or crazy behavior can tell us something about ourselves that would otherwise remain buried, hidden, and seething with menace.

Talk of what’s “genuine” and “authentic” is idle at best, metastatically brand-promotional at its worst. What happens in live theater is that one or more people contrive with gestures and speeches to convince one or more people watching them—who can be close enough to be sprayed with spittle—that what they’re saying and doing matters to anyone interested in human consciousness.

I’ve left myself open to the accusation that I’m picking on kids who are one step away from doing shows in their families’ basements. I will point out first that they are adults and professionals. Second, MinnPost is a reputable and progressive non-profit news site (one I read regularly), funded originally by the family who ran The Minneapolis Star Tribune (and coincidentally raised funds for the building of the Guthrie Theater). Third, Dr. Sherman teaches at UMN med school. Fourth, the study was published in Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, which is a journal of the American Psychological Association. Fifth: celebrity actors (like Sandra Oh) are now making sure their fans know they, too, have suffered and need therapy, not because they’re selfish and stupid like the rest of us, but because they have been charged with the gruesome task of entertaining us. Sixth: remember that Pulitzer Prize.

None of that would have moved me to my high horse, however. But as the alchemists used to say, as above, so below. The study and the article consider a microcosm that perfectly reflects the macrocosmic creative-industrial complex that has been growing since Reagan took office and began the hard work of destroying democracy. “Communities” of writers and actors snuggle in warm, softly lit seminar rooms and rehearsal spaces, and gorge on intellectual and artistic junk food, while snow falls softly on the evergreens. They know that “art” is a code-word for elitists who are opposed to the will of the people, and that the will of the people is always expressed commercially, as spiritual entrepreneurship.[11] They know that their work will speak for those who have no voice. They know that their work will show us who is bad, wrong, vicious, guilty, and who is good, right, virtuous, innocent, and who the cool kids are and who the bullies. They know their work is not condescending, false, and immoral. They know that in creative work, as in any other kind of business, centralized authority is the only way to make real money.

What they know most well, however, is this fundamental belief: voyeurism is life-affirming. The homiletic exhortations of the “nonfiction poet” relieve us of the burden of having to consume anything that isn’t a clearly labeled Lunchable Poem. Likewise the actor who warns us she’s going to chew the scenery, chews the scenery, and concludes by telling us that what was going on underneath the scenery-chewing was far darker than the glimpse we were afforded onstage. If we participate, we get a kind of emotional certificate that proclaims us allies in the finding of good in the depths of the human heart. There are no consequences. We are given a likeness of suffering that we can really enjoy, cheerfully and positively experiencing a catharsis.

But it’s not a catharsis. It’s a fix. And our dealers are far nastier than whatever you think you saw on Breaking Bad. Some of them work, e.g., at the University of Pennsylvania’s Positive Psychology Center: “Positive Psychology is the scientific study of the strengths that enable individuals and communities to thrive. The field is founded on the belief that people want to lead meaningful and fulfilling lives, to cultivate what is best within themselves, and to enhance their experiences of love, work, and play.” The top-dog there, Martin Seligman, wrote a book about the “journey from helplessness to optimism,” The Hope Circuit. By torturing dogs and inducing in them what he called “learned helplessness” (he brought his knowledge to the CIA), he found that happiness can be manufactured: once subjects have been defeated and lie in misery at your feet, you build them back up by rewarding them for compliance with state-approved consensual happiness—the happiness, that is, of the people, and the calculating, dissimulating bad actors who are their managers.

[1] One such person said to me, “You need us more than we need you.”

[2] LORT was founded in 1966 by the Managing Director of Minnesota’s flagship tourist attraction and theater museum, The Guthrie.

[4] I don’t think he’s related to the Dan Romer who wrote the “underscore” for Dear Evan Hansen, but, like, wouldn’t that be interesting?

[6] He is also the father of a young woman very active in Twin Cities’ musical theater.

[8] That’s Anne Carson. Here’s George Theodoridis: “Then, in his mind he headed off to a chariot that didn’t exist, sat on a seat that didn’t exist and struck at the horses with a whip that didn’t exist. The others around the altar didn’t know whether to laugh or cry and they asked themselves if their master had gone mad or if he was joking with them all. Then, thinking he was taking part in the Isthmian games, he stripped himself naked and began wrestling with an opponent who didn’t exist. Finally, taking the role of a herald, proclaimed himself the winner of the bout and asked the throng of spectators, which didn’t exist, to be silent.”

[9] My friend had his lead actor break a leg the day before opening night of his play. Instead of canceling the show, my friend took the part.

[11] That is actually a major at the university where I used to teach.