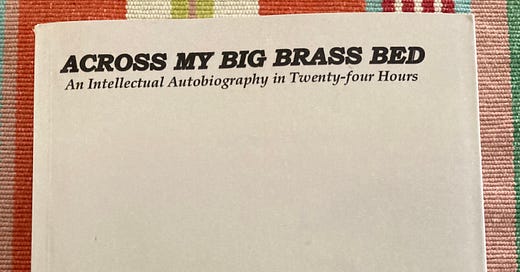

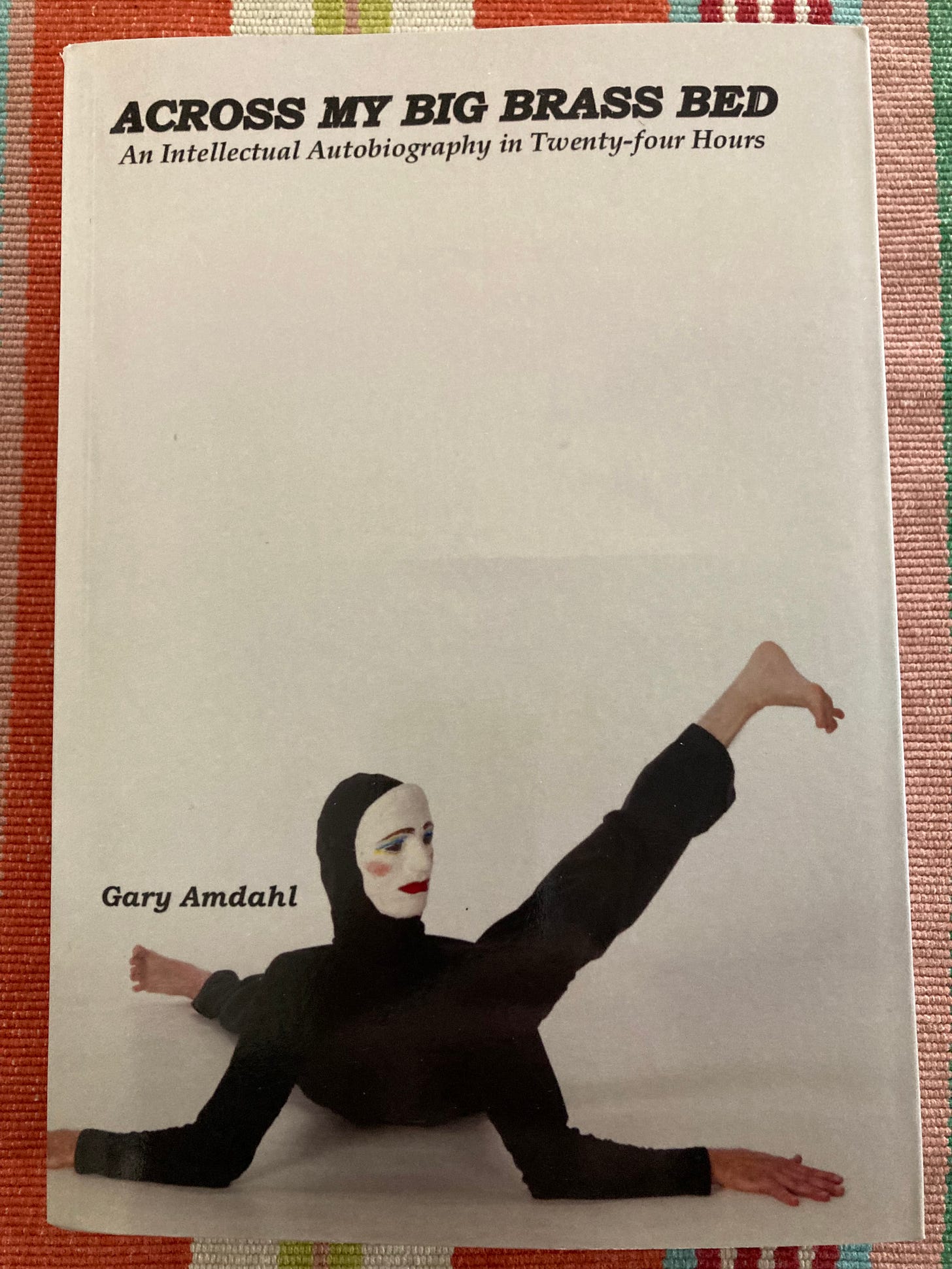

My novel, Across My Big Brass Bed: An Intellectual Autobiography in Twenty-four Hours, was republished earlier this year by a small press in Slovenia, corona/samizdat, founded and directed by Rick Harsch. It was first published in 2014, by Ryan Bradley and his Artistically Declined Press. Readers whose curiosity is piqued by the reviews below can write to the publisher at rick.harsch@gmail.com and get a free copy, shipping included. The first review is by Paul Charles Griffin, in Rain Taxi; as they are strictly a print magazine, I’ve retyped it here. The second review is by Andrew Tonkovich in the Los Angeles Review of Books, to which I’ve supplied a link.

Rain Taxi review by Paul Charles Griffin:

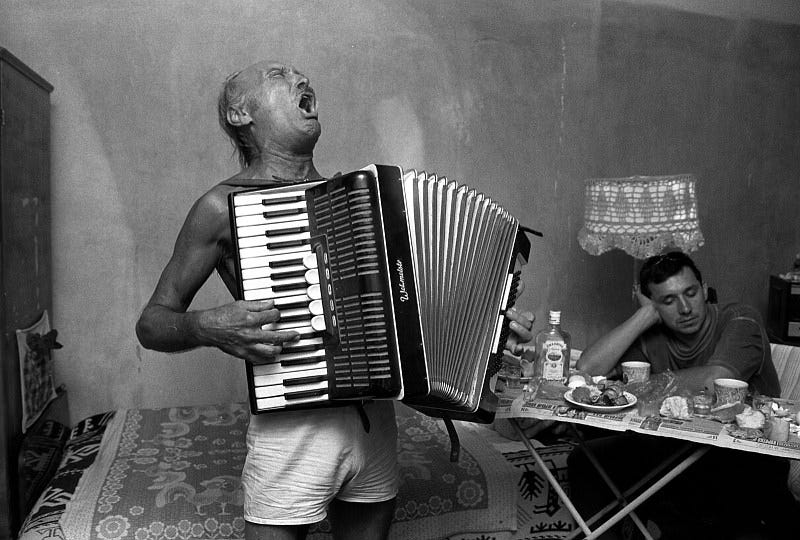

In case anyone forgot, the 1960s in America really happened. Young people tuned in, turned on, and were raised on a high-calorie diet of sex, drugs, rock and roll, and big ideas. Millions were inspired by the mercurial music of Bob Dylan, by the Open Society vision of Karl Popper, and by the dream of racial harmony of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. In his virtuosic novel Across My Big Brass Bed: An Intellectual Biography in Twenty-Four Hours, Gary Amdahl tells the story of how it felt to be a young man coming up in this feverish era. Amdahl’s unnamed narrator is a reimagined Orpheus, a rebel, a musician, an addict, and a sex god, and his tale of motorcycles, Bach, heroin, abortions, Martin Buber, and the bandonéon will astound you.

The novel’s central epiphany comes early, just after the narrator has suffered a Dylanesque motorcycle accident:

“This moment or epoch is the moment or epoch of which I will be able to say I felt confident and secure, when I felt I was me, the real me, when my deepest feelings and urges and thoughts were synchronous with my actions, when my acts were the uncorrupted syntheses of natural urge and countervailing knowledge and not a ridiculous repression of blustering bellowing but comically weak biological imperatives. I will understand how Little my happiness has to do, in stark contrast with everything I have believed up to this moment or epoch, with the rule of law, with obedience and command, with civil order and civic duty, with responsibility and stability, with authority and reason, with cultivation and faith and a wish to be as provident as God, at least to act as if I were in fact created in the likeness of God. In this moment or epoch I feel like a properly functioning human being.”

At this revelatory moment, the kid is in high school, but the idea sticks and he proceeds to chase this philosophical dragon–this “path with heart”–throughout the following four hundred pages of misadventures and mad ravings. Amdahl’s project insists on showing how thought engenders behavior, how our philosophies shape our characters. His dense block writing style–no paragraphing, no chapter breaks, just long, vaulting, energetic sentences combined with a generous deployment of italics and capitalization–places us firmly, almost violently, inside his narrator’s consciousness. You may have read stream of consciousness before, but Amdahl’s writing is a veritable Niagara Falls of prose.

While the style is compelling, the narrator’s ambitious and unconventional sex life does stretch suspension of disbelief to its limit. I kept track of his many conquests on a blank page in the back of the book, until I ran out of room. First, he is seduced by his mad, Popper-loving, heroin-smoking high school social studies teacher. This affair turns him into “a freak of nature, a sage and scholar in the body of a drug-crazed rhesus monkey.” After his teacher disappears, in his confusion and despair, he screws his therapist, convincing himself that sex is therapy. Next he sleeps with and impregnates not one but two girls his own age: Beth, the pastors daughter, and Elizabeth, his musician friend. They both have abortions without consulting him, and he is sent away to boarding school. After an honest attempt at spiritual rehabilitation, he rediscovers his old self in a sudden inspiration to seduce all four members of his string quintet. Then in the novel’s climactic moment, he beds a mother/daughter pair as well as, as he banally puts it, “another guy’s wife.” By the end of the story, alone and writing from Barcelona, he resorts to his cocktail party slogan: “I fucked on my wife’s friends, and then I fucked all my friends wives.”

Amdahl boldly writes fiction as protest and creates characters as enemies of authoritarianism in all its insidious forms. But his finest achievement here is the expert dramatization of how true comprehension often lags behind mere exposure to big ideas. Indeed Across My Big Brass Bed’s narrator spends his entire life trying to truly learn what he has already read or heard or been told. His abstract knowledge–of Popper and Dylan and Dr. King, among others–leads him to behave in certain, sometimes brilliant, often tragically confused, ways. But eventually he learns his final lesson: that real knowledge comes from experience and so is always and only a product of great sacrifice.

Los Angeles Review of Books review by Andrew Tonkovich:

https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/gary-amdahls-big-little-black-book